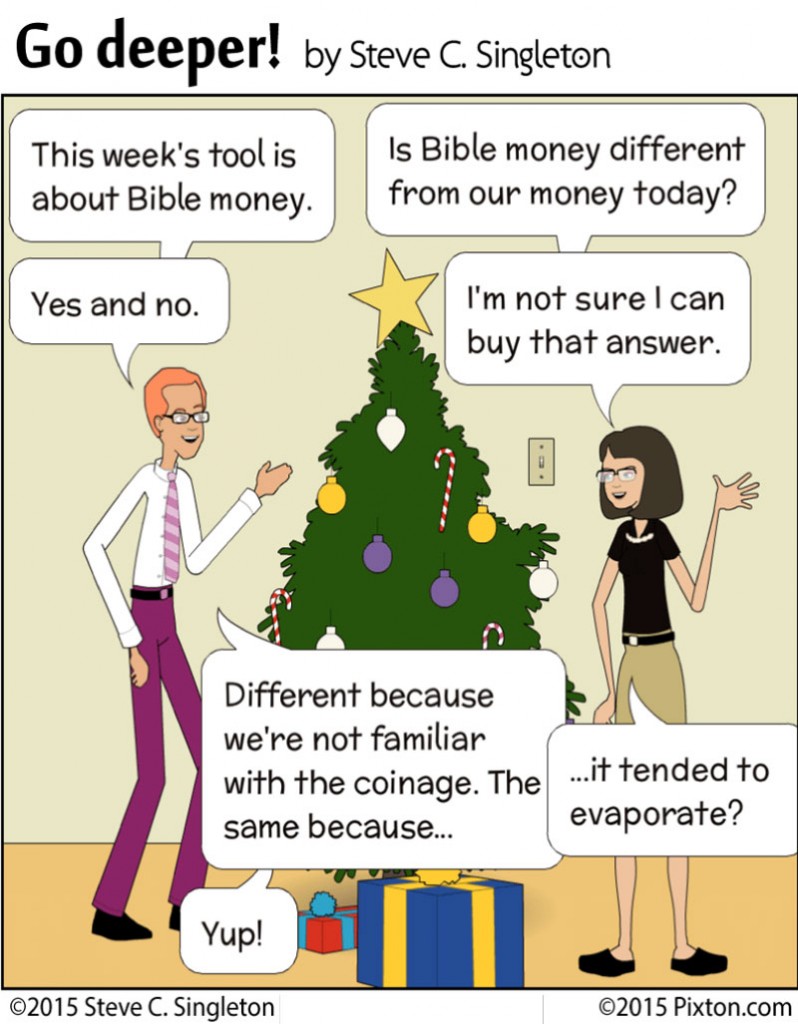

Learn the money system of Bible times to go deeper in the Scriptures

Money talks

A working knowledge of Bible coins and the monetary system of first century Palestine will help us understand the Bible better, catching us up with the original readers who could take all of these things for granted as part of their culture. We often miss the implications of references to money because we do not understand the relative values involved.

Roman and Greek coins

The Roman governments in the first century had a three-metal money system. The aureus was there gold coin, followed by the denarius made of silver, and the sestertius and lepton of bronze. One aureus was worth 25 denarii, and one denarius was worth four sesterces. Other bronze and copper coins were worth various fractions of a sestertius. Also circulating through the marketplace were Greek coins. The Greek drachma have the same value as a denarius, and the tetradrachma was worth four denarii.

Local coins

Because all of the coins so far mentioned typically bore the image of human beings, the Jews of the first century regarded them as unclean, since they ignored the prohibition against making graven images. The Hasmonean dynasty that ruled Palestine, in deference to the scruples of the Jews, minted coins that only had images of inanimate objects or plants.

The Herods continued the same practice. Their monetary system included the talent, the mina, selah, the shekel, the dinar, the prutah, and the lepton. The talent was worth 60 minae, the mina was worth 50 shekels, the shekel two dinars. As you might have anticipated, a dinar has the same value as a denarius. The dina was worth 20 prutahs, and the prutah was worth 2 lepta.

How much were they worth?

We start to get an idea of the value of these coins when we realize that the denarius was the daily wage of a common laborer. This is confirmed in Jesus parable of the Workers in the Vineyard (Matthew 20:1–16), in which the Vineyard owner agrees to pay each worker a denarius. Today a common laborer makes from $40 to $60 in a day. That would give us the approximate value of a denarius as $50. A mina, then, was worth about $5,000, and a talent $300,000.

Coins in the life of Jesus

These rough estimates, then, illuminate to money in the New Testament. For example, when Jesus tells the parable of the unforgiving servant (Matthew 18:23–35), he sets the service debt to the King at 10,000 talents (the equivalent of $3 billion) and his fellow servant’s debt at 100 denarii (about $5,000). We tend to underestimate the monetary value of both debts, but certainly the smaller debt, though significant, is only a tiny fraction of the larger. Jesus is trying to emphasize the mountain of debt we owe to God, compared to the molehill of grievances we have against anyone else.

Mark 12:41–44 tells us that as Jesus watched, a widow contributed to the temple treasury 2 lepta, combined only worth 1/20th of a denarius (about $2.50 in today’s money). Though many put in much more, Jesus praised her for giving “all she had to live on,” assessing her gift in terms of percentages rather than mere dollars and cents.

The compassionate Samaritan of Luke 10:25–37 not only patched up the wounded man he found in the middle of the road and took him to the in on his own donkey while he walked, but he also paid the innkeeper 2 denarii (about $100) for his convalescence. He promised to pay more if needed. The Samaritan’s compassion extended even to his wallet.

It makes a difference in our understanding of the Parable of the Talents (Matthew 25:14-30) to know that the master whose three servants received five, two, and one talent, respectively, was entrusting even to the one–talent man a huge sum of money. In the similar Parable of the Mina (Luke 19:12-27), though the amount entrusted is only about $5,000 each, the first and second servants returned a profit of 1,000% and 500%, earning them the rulership of ten cities and five cities, respectively.

When Jesus visited the temple, he encountered money changers in addition to those selling animals pre-approved for sacrifice (see John 2:13–17; Mark 11:15–17 and parallels in Matthew 21:12–13 and Luke 19:45–46).

These money changers were charging a fee for changing Roman and/or Greek money into the Tyrian shekel, the only coin approved for paying the annual temple tax (see Matthew 17:24–27). Because its silver content was higher than the other available coins, the rabbis gained permission from the Romans to continue minting this coin after the mint in Tyre would have been shuttered. The Romans agreed, but would not allow the Jews to change the image or inscriptions on the coin. The rabbis decided that receiving the temple tax in coins with higher silver content was more important than the offensive images on them.

Jesus might have had three objections to the practice: 1) the money changers might have been gouging their Jewish customers with exorbitant fees (He says they have made the temple “a den of robbers”), 2) the customers would have been distracted from preparing themselves to worship God by worrying about the exchange rates and the fees, and 3) the ensuing haggling over the price would be a distraction to the Gentiles, in whose court it all was taking place (spoiling the temple as “a house of prayer for all nations”).

I have not given an exhaustive list of examples of the use of money as recorded in the New Testament. Other examples include Mary’s pouring on Jesus’ head ointment estimated to be worth a year’s wages (John 12:3-8), Jesus’ object lesson with a denarius, challenging the people to give both Caesar and God their due (Mark 12:13–17; and parallels in Matthew 22:15–22; Luke 20:20–26), and the price that Judas agreed to for betraying Jesus: 30 pieces of silver (Matthew 26:14-16).

Worth more than money

Understanding the money of first-century Palestine helps us to understand our New Testament that much better. A little study pays rich dividends.

Most important in this study, however, is the emphatic question of Jesus: “What good will it be for a man if he gains the whole world, yet forfeits his soul? Or what can a man give in exchange for his soul?” (Matthew 16:26). The things of the Spirit, God’s values, are infinitely more important than all the riches of this world. Focus your attention, not on the things that perish or can be stolen from you, but on the eternal riches of God, the most precious of which is His Son, Jesus Christ (Ephesians 1:7–8, 18).

Want to dive deeper?

In Europe and the Middle East, coins were not invented as a medium of exchange earlier than around 700 BCE. This means that most references to money in the Old Testament are referring to weights of gold or silver nuggets or ingots rather than to coins.

Here is a sample of some significant money passages in the Old Testament:

Genesis 23:1-20 – Abraham buys the Cave of Machpelah as a place to bury his dead wife, Sarah. He “weighed out… 400 shekels of silver, according to the weight current among the merchants” (v. 16). This transaction took place before coins had been invented.

Genesis 37:28 – Joseph’s brothers sell him to the Midianites for 20 shekels of silver.

Genesis 42:25, 27–28, 35; 43:12, 15, 18, 21–23; 44:1, 8; 45:22 – The sons of Israel go to Egypt with silver to buy food, but Joseph returns the silver.

Other passages mentioning shekels as a weight of money:

- Silver – Exodus 21:32; Exodus 28:25; Leviticus 27:3–7, 16; Numbers 3:46–51; Numbers 7:13, 19, 25, 31, 37, 43, 49, 55, 61, 67, 73, 79, 85; 18:16; Deuteronomy 22:19, 29

- Gold – Numbers 7:14, 20, 26, 32, 38, 44, 50, 56, 62, 68, 74, 80, 86

Freewill offerings for the construction of the tabernacle and its furnishings amounted to:

- Gold – 29 talents and 730 shekels (Exodus 38:24), a little over one ton; and 16,750 shekels (Numbers 31:52), about 420 pounds.

- Silver – 100 talents and 1,775 shekels (Exodus 38:25), a little over 3-¾ tons

- Bronze – 70 talents and 2,400 shekels (Exodus 38:29), about 2-½ tons

Joshua 7:21 – Achan stole 200 shekels of silver and a bar of gold weighing 50 shekels.

Judges 8:26 – Each soldier of the Midianites give Gideon a gold earring, totaling 1,700 shekels, about 43 pounds.

2 Samuel 18:12 – A man refuses the offer of 10 shekels of silver plus a warrior’s belt for killing Absalom with the words, “Even if a thousand shekels were weighed out into my hands, I would not….” (1,000 shekels weigh about 25 pounds.)

1 Kings 10:14 (parallel: 2 Chronicles 9:13) – Solomon received 666 talents (about 25 tons) of gold per year. By today’s value of gold, that is about $851.2 million in annual income.

For additional reading

“Roman currency” in Wikipedia.

“Biblical and Talmudic units of measurement” in Wikipedia.

“Jerusalem’s Tyrian Shekel” from Beged Ivri: The research and restoration site for ancient Israelite customs.

“Roman Imperial Coins – the First Two Centuries,” from Doug Smith’s Ancient Coins (visit website)

“Coinage, pp. 149–154 in James S. Jeffers – The Greco-Roman World of the New Testament Era (1999) (Available for purchase here).

James Ross Snowden – The Coins of the Bible and Its Money Terms (1864).