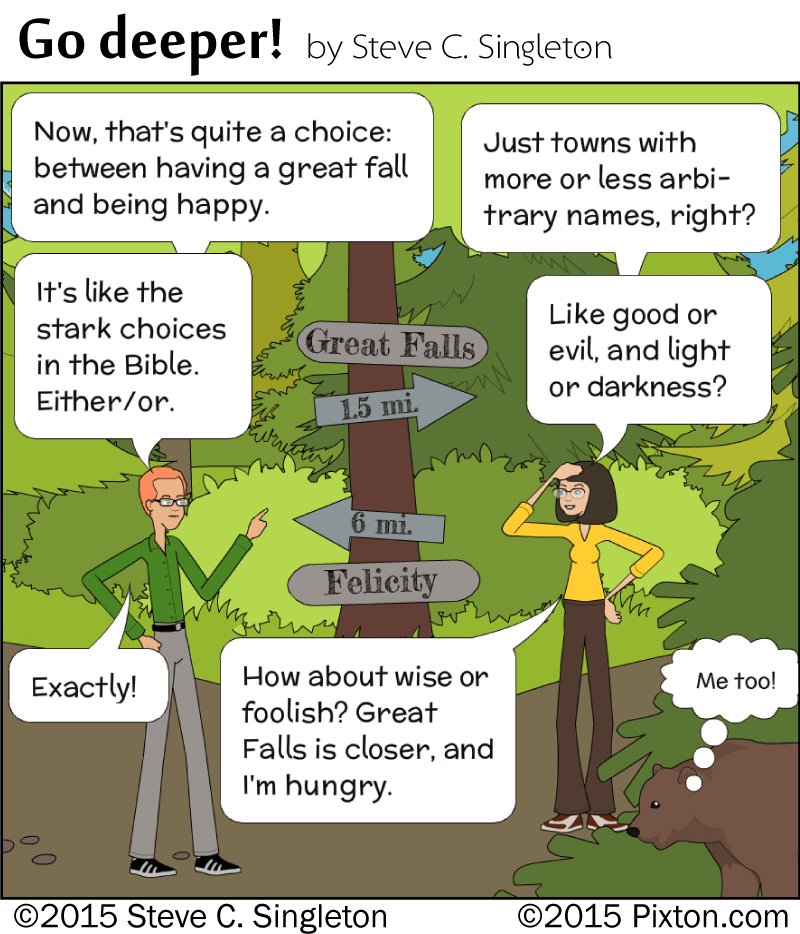

Opposites repel: How biblical dualism can help us to gain a better understanding of God’s perspective

Dualism defined

From the opening verse of the Bible we encounter terms set as polar opposites of one another: “God created the heavens and the earth.” As we continue to read, they impact us in rapid succession: light vs. darkness, God vs. humans, obedience vs. rebellion. The list of antonyms continues to grow: God vs. the serpent, life vs. death, righteous vs. wicked, holy vs. profane, clean vs. unclean, saved vs. lost, blessed vs. cursed, true vs. false, gospel vs. law, faith vs. works, and love vs. hate. These pairs, and many more I could enumerate, combine to reveal a cosmic dualism of two rival kingdoms, with everything and especially every creature on one side or the other of a great abyss that separates them.

Two rival kingdoms

Key New Testament texts describe this twofold division. For example, John 3:19-21 says:

And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God.

Or we can find this biblical dualism in 1 John 3:7-10:

Little children, let no one deceive you. Whoever practices righteousness is righteous, as he is righteous. Whoever makes a practice of sinning is of the devil, for the devil has been sinning from the beginning. The reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the works of the devil. No one born of God makes a practice of sinning, for God’s seed abides in him, and he cannot keep on sinning because he has been born of God. By this it is evident who are the children of God, and who are the children of the devil: whoever does not practice righteousness is not of God, nor is the one who does not love his brother.

In Ephesians 6:12, Paul writes:

For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.

First-century non-Christian parallels

Such a sharp divide between good and evil or between light and darkness has parallels in the first-century world. The Persian Zoroastrians believed in an eternal conflict between the good god, Ahura Mazda, and his cosmic opposite, Angra Mainyu, the source of evil. Many of the Greeks held that, not only is the body the prison of the soul as Plato taught in Timaeus, but that all things physical are tied to evil, just as all things non-physical (rational) are tied to what is good (Neo-Pythagoreans).

The Essenes, a sect of Judaism that formed an ascetic community, produced a document among the Dead Sea Scrolls entitled, The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness. Jewish apocalyptic writers portray the war between God and Satan in such works as First Enoch. The Pharisees apparently espoused a similar system of black-and-white categories, from which no one can escape (see Matt. 3:7-10; Luke 7:39; John 7:49).

Distinctiveness of biblical dualism

Yet the dualism of the Holy Scriptures is different from these, in at least three respects. First, God pronounces the physical world as “good” (Genesis 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31), not evil, a validation of creation that the Fall did not obliterate (1 Timothy 4:3-4). The distinction between physical and non-physical is not one of evil vs. good, but one of temporary vs. permanent (2 Corinthians 4:18).

Second, the prophets and the apostles allow for the possibility of apostasy (Ezekiel 18; Hebrews 6:4-8) on the one hand, and on the other, of repentance and forgiveness of sins (Isaiah 1:16-19; Titus 2:11-14)—in other words, for the possibility of moving from one kingdom to the other. The doors of the two kingdoms are not sealed; people may and often do leave one kingdom behind and enter the other (see Colossians 1:9-14).

Third, a number of passages speak of a gradual change rather than an all-or-nothing, light-switch kind of transition, drawing imagery from what happens in nature. Like the approach, dawning, and ascent of the morning sun, people can grow in their understanding (2 Peter 1:19). Like the germination, maturing, and ripening of grain, God’s Word can take root and grow in a person’s heart (Mark 4:3-9, 13-20, 26-29). Like a growing fire, God’s glory through His Spirit can shine brighter and brighter in a believer’s life (2 Corinthians 3:17-18). On the other side, like the conception, birth, and growth of an animal, sin can develop in one’s life until it dominates and enslaves (James 1:13-15).

Living in the middle

Scripture’s dualism, though real, is not its only message. We all live in what W. Sibley Towner calls “the messy middle,” between the two poles of righteous and wicked, pure and defiled, enlightened and benighted. God calls us away from sin and death, holding out that promise that “Sin shall not be your master, because you are not under law but under grace” (Romans 6:14).

Yet we still struggle with the challenge not to yield to the pull of temptation, not to offer the members of our body as servants to sin, permitting sin to resume its reign over us (Romans 6:13, 16-18). God calls us to “walk by the Spirit” (Galatians 5:16-18; Romans 8:13-14) through “the messy middle.” We make progress toward purity by His power, even as He accepts us as already having arrived.

In addition, we find Paul’s warning of the slippery-slope nature of “ever-increasing wickedness” (Romans 6:19) – or is he thinking of the crushing burden of falling into a debt with exorbitant interest, the “wages of sin” leading to death (Romans 6:23)?

These all portray both salvation and damnation as processes, in which change happens by degree. The dualism we find in Scripture is blurred by God’s grace.

Want to go deeper?

- Hebrew poetry in general and the Book of Proverbs in particular frequently employ antithetical parallelism. If we closely examine the parallel components (sometimes as many as six), we discover that the opposite elements often serve to define each other as antonyms. Even in cases where the elements are not strictly antonyms, the elements join antithetical word-clusters to enrich the meaning of the words that do appear. Before exploring more antithetical proverbs on your own, check out the following passages for an idea of what I am talking about:

Proverbs 10:32

Proverbs 9:8

Proverbs 16:30

Proverbs 27:5

Proverbs 27:6

Proverbs 28:7

- Besides the ones I listed at the beginning of this post, what other antonym pairs can you find in the Bible? Do they fit into the “Two Kingdoms” structure?

For further reading:

- Kaufmann Kohler and Emil G. Hirsch, “Dualism,” vol. 5, p. 5 in The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) (accessed October 30, 2015). The Platonic dualism of physical vs. rational, overlaid with evil vs. good by the Neo-Pythagoreans, became a popular philosophical assumption in the first century, held by Jews like the Essenes (see Josephus, Jewish War 2.154-155) and Philo (e.g., Leg. Alleg. 1.108).

- Judith Lieu, “The nature and characteristics of dualism in the Johannine corpus.” Phronema 14 (1999): 18-28.

- William W. Malandra, “Zoroastrianism: i. Historical Review Up to the Arab Conquest,” in Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition (1996) (accessed October 30, 2015).

- “Neopythagoreanism,” vol. 19, p. 378 in Encyclopædia Britannica (1911) (accessed October 30, 2015).

- W. Sibley Towner. “The dangers of dualism and the kerygma of Old Testament apocalyptic.” Word & World, 25, 3 (Summer 2005): 264-273.