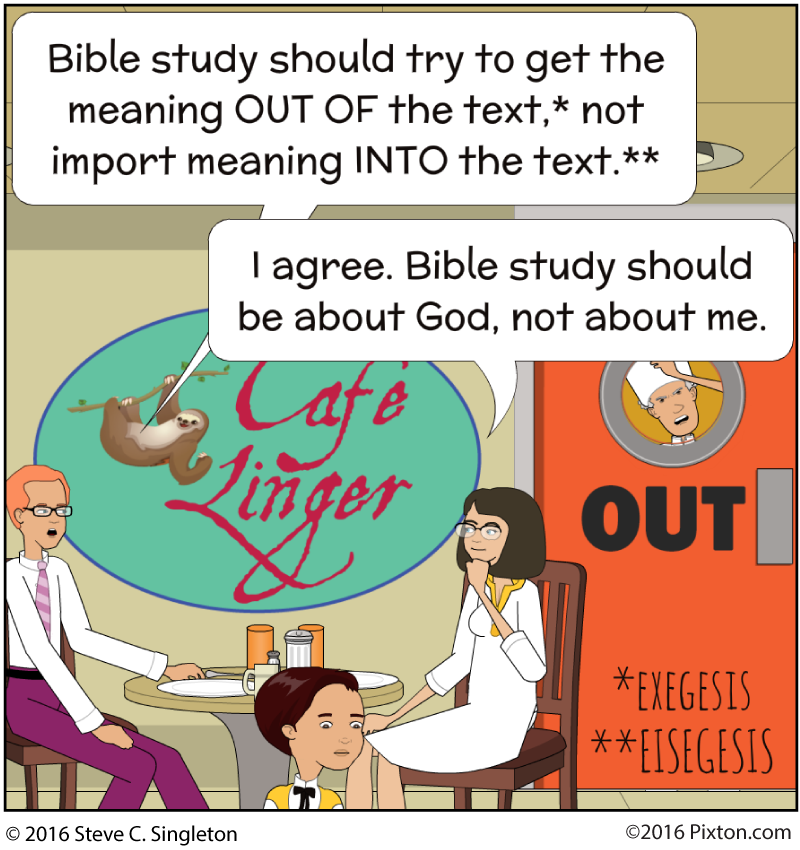

Out or in? Exegesis vs. eisegesis in Bible study

What’s the difference?

Here is a crucial question: when you study the Bible are you going OUT or going IN? In other words, are you trying to read the meaning OUT of the text or are you importing meaning INTO the text? Another way of asking it is, Are you reading a biblical text first and then forming an opinion about it, or are you starting with your opinion and then looking around for a biblical text to confirm it?

Deriving meaning OUT of carefully studying a text is called exegesis. Importing meaning INTO a text either before or after carefully studying it is called eisegesis. These two terms are based on two Greek prepositions. The preposition ek, with its object in the genitive case, means ‘out of.’ The opposite preposition is eis, which means ‘into’ when its object is in the accusative case. Exegesis and eisegesis are antonyms.

Exegesis defined

According to biblical experts Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, we may define exegesis as: “the careful, systematic study of the scripture to discover the original, intended meaning” (How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, p. 22). In his more advanced text, New Testament Exegesis: A Handbook for Students and Pastors, Fee provides us with a more extensive definition (p. 21):

[T]he historical investigation into the meaning of the Biblical text. Exegesis… Answers the question, What did the Biblical author mean? It has to do both with what he said (the content itself) and why he said it at any given point (the literary context). Furthermore, exegesis is primarily concerned with intentionality: What did the author intend his original readers to understand?

Naturally, you will assume that exegesis is hard work. Some fall into the habit of eisegesis simply because they are too lazy or too much in a rush to be effective exegetes.

How can we tell if we’re doing eisegesis?

Many people who are guilty of eisegesis are unaware of their disastrous methodology. Without carefully examining their assumptions, they use these assumptions to shape the meaning of one text after another. Their Bible study tends to be of the buffet-salad variety: they select a verse here (isolated from its context) and other verses there and elsewhere and then try to mash all of them together. All of us should remember the maxim: a text wrested from its context becomes a pretext.

Three examples of eisegesis

A notorious example of this kind of eisegesis is the following chain of passages: “Judas… went away and hanged himself” (Matthew 27:5). “Go and do likewise” (Luke 10:37). “What you are about to do, do quickly” (John 13:27). These three verses are unrelated to each other, but throwing them together in this haphazard way almost sounds credible.

Here is an example I heard during a talk before the men collected the contribution. “The Lord has commanded us, ‘Upon the first day of the week let every one of you lay by him in store, as God hath prospered him, that there be no gatherings when I come.’ As we wait for the Lord’s return we should obey his command to be generous givers.” The speaker apparently failed to realize that the apostle Paul was speaking of his pending return to Corinth, not Christ’s second coming.

I once heard a knowledgeable Christian claimed that Jesus went temporarily insane while on the cross. When I asked him what was the basis of this opinion, he quoted Isaiah 53:8, “he was taken from prison and from judgment” (KJV). This verse does not mean that Jesus lost his reasoning ability during his crucifixion. Being taken from judgment correctly refers to the unjust procedures by which Jesus was wrongfully convicted.

A particular danger for preachers

In the press of weekly sermon preparation and under pressure for his sermons to be original and not redundant, preachers can easily fall into the trap of eisegesis instead of exegesis. Here are three examples of how this mistake can happen.

- Interpreting historical events metaphorically – this seems to be especially easy when preaching on the miracles of Jesus. Many of us have heard the sermon, “Get out of the boat,” in which preachers use Peter’s willingness to come to Christ walking on the water as an example for us to overcome our timidity. Preachers sometimes apply the calling of the storm to Christ’s ability to bring peace to a troubled soul. Although many actions can serve as positive and negative examples for us, it is easy to cross the line and transform a historical narrative into a parable.

- Applying an unusual definition to the meaning of a word in a different context – For example, the prolog of the Gospel of John calls Jesus the Word (see also Revelation 19:13). Would we be right, however, to apply this unusual definition of ‘word’ to passages like Psalm 119:9, 11, 16, 17, 28, 37, 42, etc.? What about Romans 10:8: “the word is near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart”? Does it mean Christ is near you?

- Distorting the meaning of a verse in context to make it fit one’s homiletical agenda – Preachers a generation ago used to preach on the need for having a long-term goal for a congregation, using as a text Proverbs 29:18: “Where there is no vision, the people perish” (KJV). They should have recognized that they were misusing this text because of the rest of the verse, “… but he that keepeth the law, happy is he.” ‘Vision’ in this context is not referring to long-term planning, but to a miraculous prophetic revelation of the will of God. Some modern translations add the word ‘prophetic’ to help clarify: “Where there is no prophetic vision the people cast off restraint, but blessed is he who keeps the law” (ERV).

Are you in or out?

One of the main ways of guarding against this mistake is to ensure that you ask these questions regularly:

- Does my immediate understanding of this passage fit the context?

- Do I sincerely want to learn what this text meant for its original readers?

- Am I starting with an idea in defense of which I am bending passages, or am I modifying my idea to fit the verses I have discovered?

Do you want to dive deeper?

Take a look at the following resources for further study:

Donald A. Carson. Exegetical Fallacies. 2d ed. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 1984.

Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart. How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth. 3d ed. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2003.

Gordon D. Fee. New Testament Exegesis: A Handbook for Students and Pastors. 3d ed. Philadelphia: Westminster, 2002.

Ronald Sider. Scripture Twisting: 20 Ways Cults Misread the Bible. 2d ed. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1994.

“Eisegesis” (Wikipedia article)

“What is the difference between exegesis and eisegesis?” (article at GotQuestions.org)